The Doge Sword (#1373)

The Doge (generally translated as “Duke”) was not, unlike most positions of power in Europe at the time, a hereditary office. The Doge was elected for life, it was true, but was forbidden from choosing a successor.

Hand forged from 5160 High Carbon Steel

Hand forged from 5160 High Carbon Steel

Differential Hardened at a Rockwell of 60 at the Edge; 48-50 at the core.

Fittings: Mild Steel

Handle: Leather Wrapped Wood Core

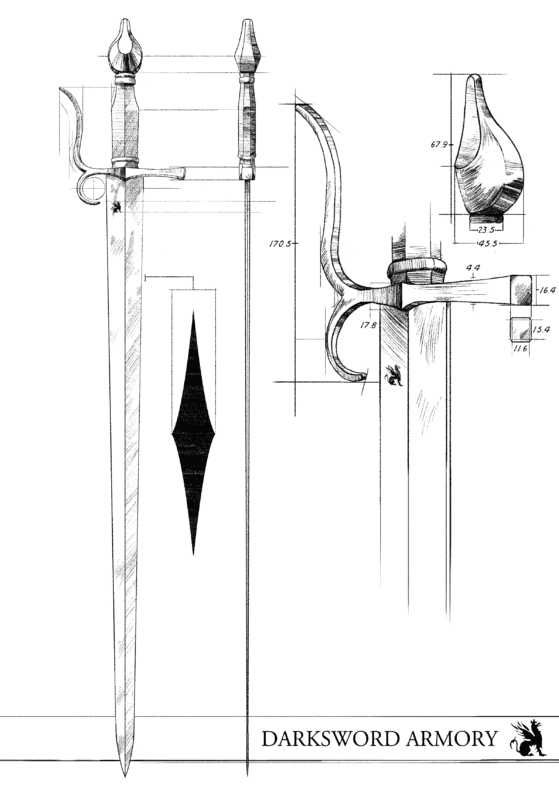

Total length: 40″

Blade length: 32.5″

Blade width at base: 1.85″

Grip Length: 4.5 inches

Weight: 2 lbs 13 oz.

POB: 4.5 inches

CAD827.05 – CAD973.00

The Republic of Venice was distinct from many other European states for several reasons. For one, it had an almost unheard-of longevity – the Republic existed as a political and for over a thousand years, from the 7th to the 18th centuries, when many other nations rose, fell, and faded to obscurity. For another, it had a unique governing structure; whereas many nations during its thousand-year existence were ruled by monarchies of varying levels of control and influence, the Republic was overseen by the Great Council of Venice. This parliament was composed of a hereditary ruling class of powerful merchants and aristocrats who together created laws, elected the Council of Ten (the leaders of the city-state), and the elected the head of state – the individual known as the Doge of Venice.

The Republic of Venice was distinct from many other European states for several reasons. For one, it had an almost unheard-of longevity – the Republic existed as a political and for over a thousand years, from the 7th to the 18th centuries, when many other nations rose, fell, and faded to obscurity. For another, it had a unique governing structure; whereas many nations during its thousand-year existence were ruled by monarchies of varying levels of control and influence, the Republic was overseen by the Great Council of Venice. This parliament was composed of a hereditary ruling class of powerful merchants and aristocrats who together created laws, elected the Council of Ten (the leaders of the city-state), and the elected the head of state – the individual known as the Doge of Venice.

The Doge (generally translated as “Duke”) was not, unlike most positions of power in Europe at the time, a hereditary office. The Doge was elected for life, it was true, but was forbidden from choosing a successor – this eliminated the possibility of the office becoming a monarchy. The position was not one that provided great wealth or influence; in fact, the Doge was prevented from owning any foreign land, and after the Doge’s death his family was liable for any crimes he had committed in office (presumably as a method of inspiring honesty and integrity). In later years the power of the Doge declined, and though it became a largely symbolic office there were still benefits to ruling Venice – one of which was the ability to live in the Doge’s Palace.

The Doge’s Palace (Pałaso Dogal in Venetian) is an excellent example of Venice’s take on Gothic architecture. While several iterations of the Palace existed through the years (rebuilt due to age, changes in government, and several notable fires), most of the current structure was completed in the 15th century. After the end of the office of the Doge in the late 18th century, the Palace remained in use by various branches of government for the next century. In 1923 the last public office was removed from the building, and the restored Doge Palace entered its next stage of existence as a museum. The museum, in addition to its breathtaking construction and frescos, contains numerous works of art and artifacts from Venice’s history – including a breathtaking collection of medieval and renaissance swords.

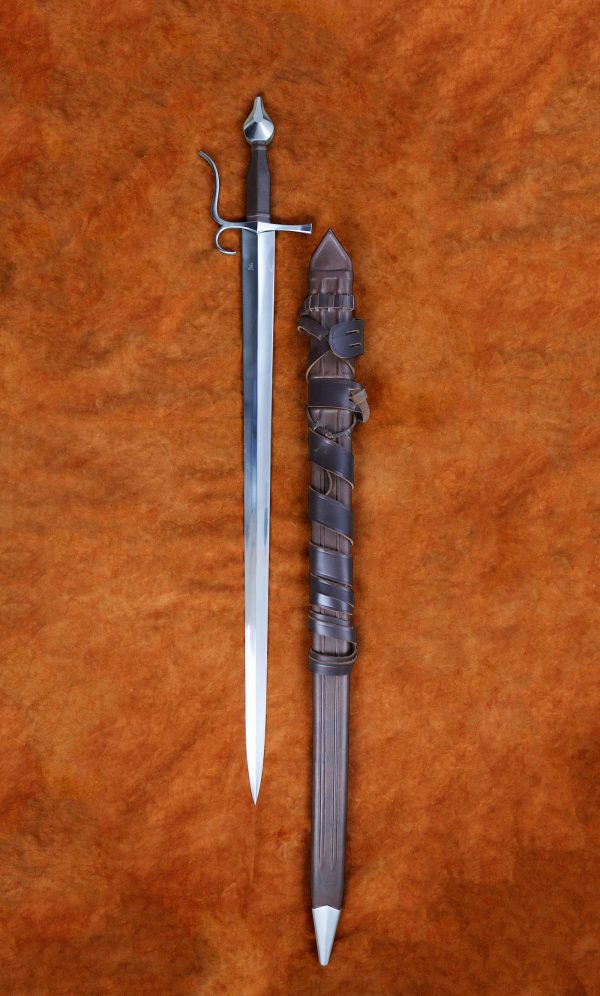

The Darksword Armory Doge Museum Sword is based on surviving examples with the Doge museum. Its curved guard with finger protector is common on swords form this area of Europe, and the distinctive-shaped pommel sets it apart from other medieval and renaissance swords. Travelers to Venice will recognize this unique pommel and guard combination from several swords in the Doge collection. The blade chosen for this particular representation is hollow ground with a stiff spine, allowing for good flexibility but retaining the ability to make a firm thrust. The blade’s long, tapering point is common among many blades of the 15th century, which were adapted to thrust into the gaps of full plate armor. An oxblood leather wrapped handle completes the weapon, which would certainly look at home on the hip of any Venetian who walked the streets of one of the longest-lasting republics in history.

Be the first to review “The Doge Sword (#1373)” Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Related products

Medieval Swords

Arming Swords

Broadsword

Arming Swords

Medieval Swords

Medieval Swords

Broadsword

Fantasy Swords

HEMA Swords, WMA Swords and Weapons

Medieval Swords

Longsword

Fantasy Swords

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.