-

×

Jousting Helm Stechhelm (#1731) 1 × USD1,200.00

Jousting Helm Stechhelm (#1731) 1 × USD1,200.00 -

×

Wallace Collection Bascinet (#1748) 1 × USD450.00

Wallace Collection Bascinet (#1748) 1 × USD450.00 -

×

1763 Templar Shield 1 × USD475.00

1763 Templar Shield 1 × USD475.00 -

×

Gothic Gorget (#1710) 1 × USD75.00

Gothic Gorget (#1710) 1 × USD75.00 -

×

Medieval Shields 1 × USD475.00

Medieval Shields 1 × USD475.00 -

×

1757 French Royal Shield 1 × USD475.00

1757 French Royal Shield 1 × USD475.00 -

×

1764 Teutonic Shield 1 × USD475.00

1764 Teutonic Shield 1 × USD475.00 -

×

1761 Medieval Crusading Knight Shield 1 × USD475.00

1761 Medieval Crusading Knight Shield 1 × USD475.00 -

×

1767 German shield 1 × USD495.00

1767 German shield 1 × USD495.00 -

×

1766 English Aristocrat shield 1 × USD475.00

1766 English Aristocrat shield 1 × USD475.00 -

×

1762 Templar Shield 1 × USD475.00

1762 Templar Shield 1 × USD475.00 -

×

1760 Medieval Battle shield 1 × USD475.00

1760 Medieval Battle shield 1 × USD475.00 -

×

Mjölnir Hammer of Thor Pendant (#4021) 1 × USD95.00

Mjölnir Hammer of Thor Pendant (#4021) 1 × USD95.00 -

×

Stiletto (88107) 1 × USD300.00

Stiletto (88107) 1 × USD300.00

Tracking the Medieval Arms Race

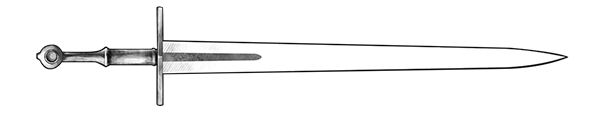

Ewart Oakeshott’s (1916-2002) typology is far more than just a means for cataloguing variations on the Medieval sword. It also tells a story – a chronicle of an arms race centuries ago that pitted armorers against bladesmiths in an ongoing battle to push military technology to its limits.

One cannot truly understand the development of swords without understanding the arms race – no sword was ever developed in a vacuum. The swords of the Middle Ages were precision weapons, built to function on a battlefield against the armor of its day, and defeat it. As development in armor made one type of sword blade obsolete, bladesmiths would make another to take its place.

Oakeshott’s typology is a journey through time and the history of Medieval warfare, from the Viking Age to the Renaissance, from raiders to armored knights to the sword masters whose work still inspires historical fencers today. And it all begins as the age of longships faded away and a new feudal order emerged.

The Rise of the Age of Chivalry

The first period of Oakeshott’s typology began in the wake of a technological revolution that began in Germany. Beginning most likely with the Ulfberht forge – the 10th century equivalent of a sword factory or firm – bladesmiths discovered how to refine steel to the point that they could make a blade out of a single bar, rather than having to use the time consuming (albeit beautiful) process of pattern welding. The Ulfberht forge even created swords from high grade crucible steel, a feat unmatched in Europe until long after the Middle Ages, although these swords ceased to be produced once the trade route providing the steel was lost.

The armour of the period from roughly the 10th to 14th centuries – a timeframe that saw the end of the Viking Age and dawn of Feudal Europe – was marked by nobility and knights wearing mail armour, while infantry tended to wear linen gambesons, if they wore any armor at all. The sword of this period was the knightly weapon of last resort – if the knight drew his sword, it meant that the cavalry charge had failed and the knight was now surrounded by enemies.

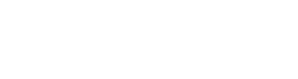

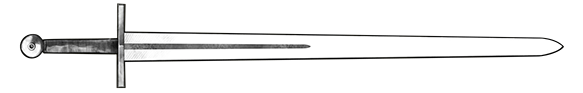

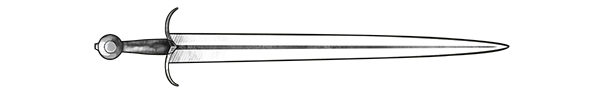

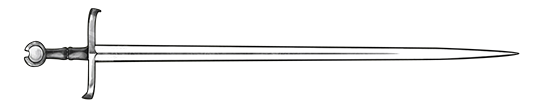

The sword of this time was primarily a cutting weapon, used to strike down at lightly armored oppenents from horseback, and its blade forms reflect this. The earliest, the Type X, straddles the Viking Age and the feudal world that followed. The edges are almost parallel, with a long, deep and wide fuller, and a tip that can thrust, but is clearly not made to punch through heavier armour. This type of sword is made until the 12th century, but is not made after 1200 AD.

The fullers of the type X were very wide, but at the same time there was a variant with a thinner fuller, which Oakeshott named the type Xa. The Xa swords were common throughout the same period as the type X swords, beginning to appear around 1000, and are only really distinguished from them by the narrower fuller, and occasionally longer blade length.

Some of the sword blades became longer as time went on – the type XI is a key example. The blade form itself is very similar to the Xa, but it tends to have a much longer, and a bit narrower, blade in relationship to the handle. The narrow fuller runs almost to the tip of the blade. These swords have an acute point, being built a bit more for thrusting than the previous ones, although cutting was still the sword’s primary purpose. The majority of the type XI swords were used between 1100 and 1175.

The type XI also has a subtype, the XIa – this sword appears in a number of sculptures dating from 1250-1350. The main difference between the two is the width of the blade – like the XI, there is still a long, narrow fuller running almost to the tip, but the blade itself is wider than the XI.

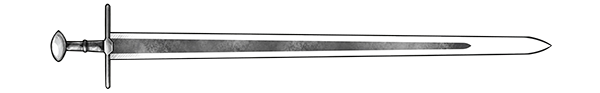

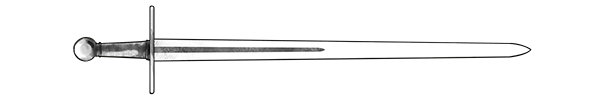

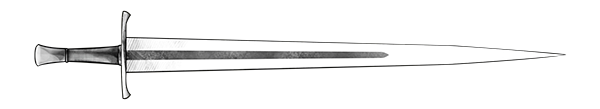

With the type XII, what we often think of as the knightly sword begins to emerge. These swords, which tend to date from the beginning of the 13th century to at least the mid-14th century, are marked with a tapering broad and flat blade, with at least one fuller extending down 2/3 to 3/4 the length of the sword. This is a sword where thrusting has become more important, but the cut is still paramount.

With the type XII’s variant, the XIIa, we see the dawn of the “Sword of War,” or “Great Sword.” These were swords that had a longer handle that could be used with two hands instead of one. The blade remains similar to the XII, but is longer. This also appears in the 13th and 14th centuries.

The type XIII and its subtypes, the XIIIa and XIIIb, are perhaps the most famous of all the sword types in the Middle Ages. These are the swords of war, sometimes known as a “Great War Sword” or “big German swords.” This seems to be an originally German type of sword, although it is one that is seen and used across Europe. The blades have almost parallel edges, with a rounded tip and a fuller that only extends halfway down the sword. The XIIIa swords could be true two-handers – the length of the blades ranged from 32-40″, with a handle that could be anywhere from 6-10″. The XIII had a shorter blade and handle, while the XIIIb had a longer blade, but a shorter handle. All of these swords appear between the 13th and 14th centuries.

With the Type XIV, we find a shorter sword, with a blade that was often between 28-32″ long, quite broad and flat, and tapering down to a fine point. The fuller often extended only halfway down the blade, although there are exceptions, and multiple fullers do appear. This sword was very popular for a short period of time – it only appears between 1275-1340.

The Advent of Plate

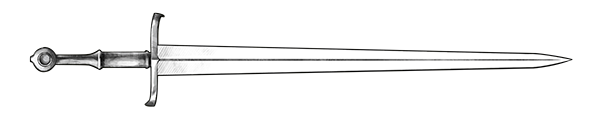

By the end of the 14th century, the science of armor had advanced, and the design of the sword needed to adapt or become obsolete. The mail armor that had typified the knightly classes, against whom knights were so often using swords to fight, had been supplanted by plate armor, a process that took the better part of a century. While a sword could do considerable damage to a man wearing mail from force alone, the advent of plate rendered cutting swords next to useless against an armored foe.

To adapt to this new armor, bladesmiths began to make thrusting swords that were stiff instead of flexible, with diamond cross sections that would reinforce the tip. These were swords that were built to thrust through the gaps in armor, or even through the armor itself. The act of cutting had become a minor concern at best in the technology of the sword, at least those that were designed to deal with plate.

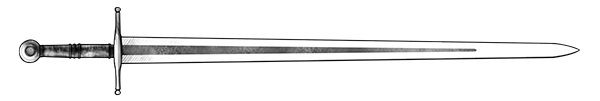

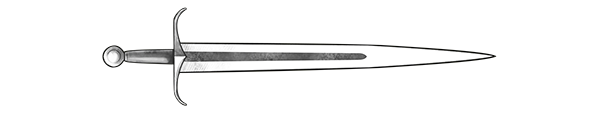

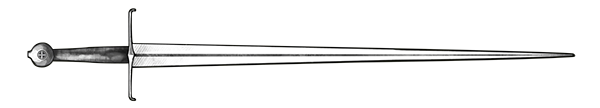

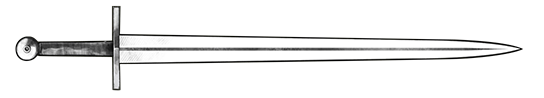

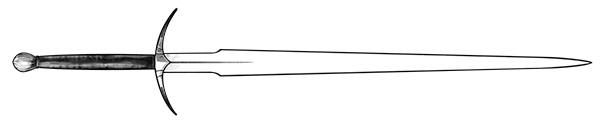

In the type XV and its XVa subtype, we see this new weapons technology take shape. The blade is stiff and has a triangle-shaped profile, with a diamond cross section and no fuller. As with the previous sword types, the XVa subtype is marked with a longer blade and handle, often called a “Bastard sword.” This is also a long running and popular sword types of the Middle Ages, with examples dating from 13th century all the way to the late 15th century.

While the type XV and XVa were built for fighting against an opponent armored in plate, this does not mean that there was not a transitional period, with armorers experimenting with new forms of armor while bladesmiths created swords to counter them. In the type XVI and its XVIa two-handed subtype, we see an example of one of these transitional swords. This was a type of sword built to attack reinforced mail between 1300-1350. The blade is a combination of a cutting and thrusting sword. The upper half of the blade is broad, flat and fullered. The lower half is stiff and acutely pointed, with a reinforced diamond cross-section, although XVIa swords exist with a hexagonal cross-section.

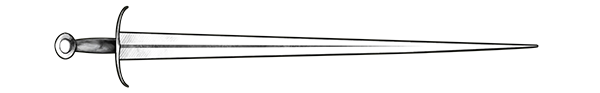

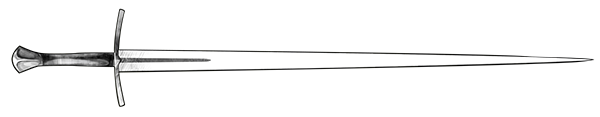

With the type XVII, used between around 1360-1420, we see a sword designed for no other purpose than cracking into plate. The blade is long, stiff, and triangular in profile, with a hexagonal cross section – more of a very long spike with a handle than a sword. The handle always had a hand-and-a-half grip.

Forward into the Renaissance

It is tempting to depict the development of the sword as reacting solely to the development of armor, but this was not all that sword design reacted to – while the use of plate armor had rendered the cutting sword obsolete and created the need for a “plate cracker,” for lack of a better term, other developments in the lead-up to the Renaissance would change the way swords were made, and restore the act of cutting as a clear and present concern.

The first of these developments was the democratization of the sword. The sword had been the weapon of the knightly classes. As the economy of Medieval Europe developed, however, it became possible to equip infantrymen with swords as well. These infantrymen would not necessarily be up against opponents in plate, and they needed swords that could both cut through lighter armor, but still handle plate if they had to face a mounted knight.

The second of these developments was the rise of the sword masters. From the 14th century onwards, the sword began to be used not just as a battlefield weapon, but as a civilian weapon as well. Starting in Germany and then Italy, sword masters such as Johannes Liechtenauer (14th century) and Fiore dei Liberi (c. 1340s-1420s) trained students in the use of the sword, not on the battlefield but in the judicial duel against unarmored and armored opponents. This too required a sword that could both cut and thrust.

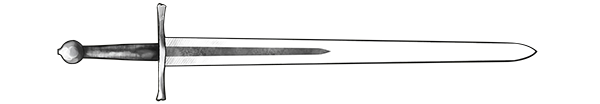

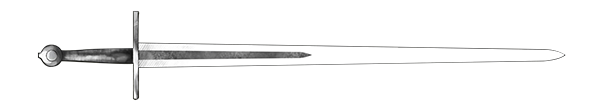

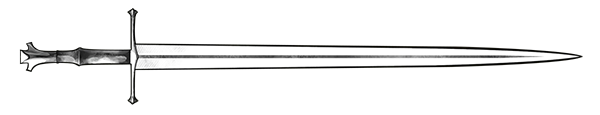

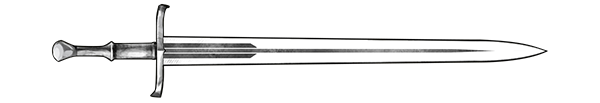

With the type XVIII and its five sub-types, we see the development of a true cut-and-thrust sword, and one of the most successful sword types in Europe, used from the 14th century even into the 19th century. The blade has a diamond cross section, sometimes with a raised ridge for additional stability, with a wide base tapering to an acute point. The longer, two-handed XVIIIa variant had a similar, but longer blade and handle, often with a fuller running 1/3 of the way down the blade.

Unlike the other swords, the XVIII has four additional variants. The XVIIIb is a long, two-handed sword with a very long handle, often as long as 10-11″. The XVIIIc was a shorter-handled sword, usually with a hand-and-a-half type grip, with a longer blade. The XVIIId was similar to the XVIII, but with a more slender profile and a single-handed grip. The XVIIIe is a 15th century Danish sword two-handed sword, marked by a narrowed ricasso.

The type XIX is an outlier in many ways – the swords of this type that remain are very distinctive, appear to have come from the same workshop, and represent a transitional phase between the Medieval and Renaissance sword. Dating from around 1350-1400, the XIX is a single-handed sword, with a mostly parallel edge turning into an acute point. The blade has a hexagonal cross section with a fuller running roughly halfway down the sword. What is unique, however, is the presence of a ricasso – at the hilt of the sword is a short ricasso, with two grooves engraved on the ricasso on each side of the fuller. This facilitated a method of holding the sword where the forefinger was wrapped around the guard, a method popular enough that at least one of these swords has been found with a finger ring on the guard – one of the earliest examples of a complex hilt.

The type XX and its sub-type XXa is a sword marked by its fullers. Used mainly in the 15th century, but sometimes in the 14th century, both the XX and the XXa are long hand-and-a-half swords with parallel edges that come to a point. However, this type tends to have three fullers, one central fuller running at least halfway down the blade with a shorter fuller on each side. The main difference between the XX and its XXa subtype lies in its blade shape – the XXa is more tapered, with an acute point.

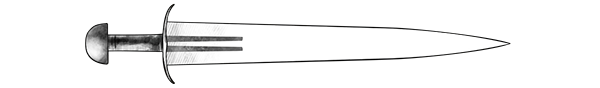

With the type XXI and XXII, we reach the end of the Middle Ages, and the beginning of the Renaissance. Both are single-handed swords with a wide blade tapering down to a graceful point, used in the 15th century. The XXI is the Italian Cinquedea, or “Five Fingers.” This tends to have multiple fullers and a triangular blade profile. The XXII is a similar sword, although it is marked by two short, deep and narrow fullers.

As Oakeshott noted in Records of the Medieval Sword, once the Renaissance begins, the typology must end – the swords of the Renaissance were so varied in form and function that a typology based on blade profile and cross section simply fails as a tool. However, from 1000 to 1450, Oakeshott’s typology gives us a fascinating look into the world of the Medieval sword and its development.

Bibliography

Chad Arnow, Russ Ellis, Patrick Kelly, Nathan Robinson, and Sean A. Flynt, “Ewart Oakeshott: The Man and His Legacy: Part II.” MyArmoury.com, 2006: http://www.myarmoury.com/feature_oakeshott2.html

Bjorn Hellqvist, “Oakeshott’s Typology – An Introduction.”: http://www.algonet.se/~enda/oakeshott_eng.htm

Ewart Oakeshott, The Archaeology of Weapons, Barnes & Noble Books, 1994 (originally published, 1960).

Ewart Oakeshott, Records of the Medieval Sword, The Boydell Press, 1991.