-

×

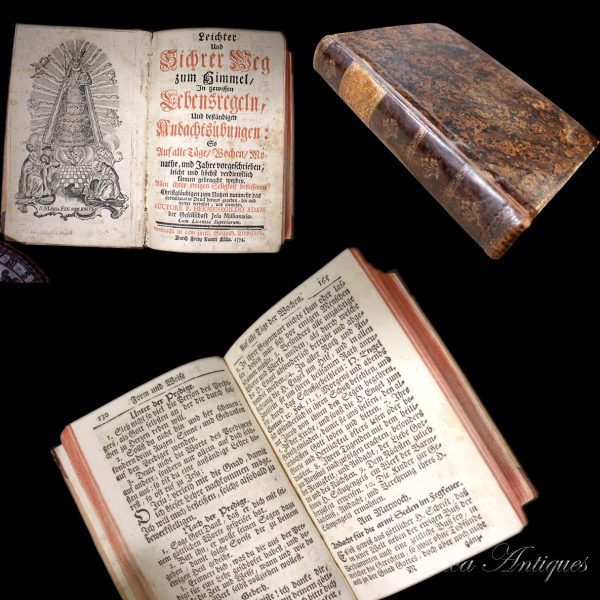

1773 Occult Possessed Holy Water and Witches - German Catholic Way to Heaven (88125)

1 × CAD350.25

1773 Occult Possessed Holy Water and Witches - German Catholic Way to Heaven (88125)

1 × CAD350.25 -

×

German Smallsword, 1720 (88106)

1 × CAD840.60

German Smallsword, 1720 (88106)

1 × CAD840.60

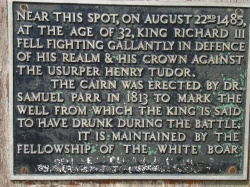

The story of the Battle of Bosworth takes on an added newsworthy significance at the present moment. Not only was it the last battle in the “Wars of the Roses” but it was also a major historical point as it was the last time a reigning monarch, in this instance Richard III, went into battle for his country.

The story of the Battle of Bosworth takes on an added newsworthy significance at the present moment. Not only was it the last battle in the “Wars of the Roses” but it was also a major historical point as it was the last time a reigning monarch, in this instance Richard III, went into battle for his country.

On February 4th 2013, it was revealed that the bones discovered buried under a car park in Leicester city centre in August last year are actually those of Richard III.

Background to the wars

The roots of the Wars of the Roses lay much further back than many people assume, for while the actual series of battles commenced around the year 1455, the beginnings of unrest start around the death of King Edward III and the power play that formed between his sons who were all anxious to rule.

Edward III’s eldest son, the Black Prince, Edward had predeceased him by just a year and so the crown automatically passed to his grandson, the then ten year old Richard II.

However, as was customary for the time and because of his tender years, Richard’s uncle and the Black Prince’s brother, John of Gaunt ruled in his name. As Richard entered his teens he became increasingly embittered about the way in which John was ruling and started to rebel against the decisions he made. Richard’s own style of governance, was however, deemed unsuitable by most of the upper echelons of the ruling elite.

After John of Gaunt’s death in 1399, Richard confiscated his lands. As an act of revenge, Gaunt’s son Henry Bolingbroke raised an army to usurp Richard, which was successful. He took the throne as Henry IV and had Richard imprisoned in Pontefract Castle, where he died, possibly from being starved to death in 1400, the method of death was such that in the event of his body being inspected, there would be no suspicious marks to suggest foul play.

As Bolingbroke was not the natural successor to the throne, there were naturally many challenges to his right to rule, however, at the time of his death in 1413 the country was in a relatively peaceful state and, as such, his leadership passed to his own son Henry V. It was when Henry V’s son, Henry VI took the throne after the former’s death from dysentery in 1422, that signs of real unrest began to surface.

Henry VI: the weakest link?

History has generally not been kind to Henry. Coming to the throne at just four months old in 1422, by the time he reached maturity he was a young man who was seen to be not only a weak ruler but dominated by his wife, the forceful and fearsome Margaret of Anjou.

He was also the disputed leader of France for most of the length of his reign, but frequent bouts of what was termed at the time “insanity” meant that for many years he was in a catatonic state, unaware of his surroundings or what was going on in his kingdom.

This led to Yorkist factions seeking to try and usurp Henry and put their own claimant on the throne. The first real battle of the conflict took place in 1455 and was led by Richard, Duke of York. The King was defeated in battle, which brought on another attack of mental instability and Richard became protector of England. During the next four years there were more battles and skirmishes for supremacy until Richard was finally killed at the Battle of Wakefield in 1459.

Edward IV and his Queen

These were unsteady and unsafe times in England and The House of York finally gained control of the throne in 1471, after both Henry VI and his son Edward were killed after the Battle of Tewkesbury.

Edward IV ascended the throne and began to rule with a rod of iron, ruthlessly punishing anyone who failed to submit to his rule. When he died in 1483, the crown passed to his twelve year old son, also Edward, with the late King’s brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester as protector.

A story emerged that the late King had been pre-contracted in marriage to someone else other than the Queen thus rendering his marriage and children illegitimate. Therefore, Richard took it upon himself to seize the reins of power and elect himself as King, becoming Richard III.

The Battle Of Bosworth

In 1485, Henry Tudor was preparing to set sail from France with a not inconsiderable army of two thousand troops to help him gain the English throne. On the 17th August he arrived at Milford Haven from Harfleur and began a march through Wales to gather more men.

In 1485, Henry Tudor was preparing to set sail from France with a not inconsiderable army of two thousand troops to help him gain the English throne. On the 17th August he arrived at Milford Haven from Harfleur and began a march through Wales to gather more men.

It is said that at some point on his journey towards Bosworth he had considered giving up and going back, but after a meeting with one of his adversaries Lord Stanley, decided to forge ahead. This one decision, though he didn’t know it at the time, changed the course of English history.

By contrast, Richard had a much stronger showing in terms of numbers. It is estimated he had around twelve thousand troops at his disposal. However, around a quarter of that number, it is suggested, had divided loyalties as they were commanded by the Stanley family who were known turncoats and wont to change their allegiance to whosoever would give them the most power and money.

Richard had stationed himself in Nottingham, meaning that wherever Henry struck from, he would be able to travel relatively quickly to fight him.

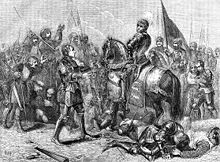

On 22nd August 1485 the armies met in the village of Market Bosworth. The suspect Stanleys found their positions at the north and south of the battlefield, whilst the King decided he must advance from Ambion Hill.

Henry Tudor sent his men to attack the enemy formation under the experience of the Earl of Oxford. Henry was hoping that the Stanleys would surrender and join him, but they kept themselves non-committal to either side, despite Richard having Lord Stanley’s son prisoner.

King Richard’s men responded to Oxford’s attack with a stream of artillery fire, which caused the Earl of Oxford to change his position. Oxford then began to attack the Duke of Norfolk’s division; retaliation from Norfolk meant that Oxford and his men were pounded by arrows from a team of skilled archers.

Significant intelligence was brought to Richard, informing him that Henry Tudor was about to attack. Richard therefore led an “all or nothing” charge that was aimed at killing Henry, but in the ensuing battle the Duke of Norfolk was killed. Richard was urged to try and retreat, but decided to go under his own steam and carry on.

At this point, Tudor’s standard bearer William Brandon was killed and it was here that the previously non-committal Stanleys decided to try to put an end to the battle by aligning themselves on the side of Henry.

They engaged with the King’s men and cut Richard off from his troops. Many of his men were cut down on the battlefield to cries of “TREASON!”. The few loyal to him were killed as they tried to save their monarch, before he too was found, dismounted from his horse and killed. Once the monarch was dead, the remnants of his army retreated.

According to the writings of Polydor Vergil, in comparison to other battles of the time, Bosworth was relatively short, only lasting for around two hours.

The aftermath of battle: a thorny crown

The romantic image of Richard’s crown, plucked from a nearby hawthorn bush and presented to the new King Henry VII is one that is not necessarily true but has survived the centuries. The truth is rather less wholesome.

Richard’s body was paraded unceremoniously and ignominiously through the streets to prove his death and show the colours of the new king. Henry further cemented his grip by marrying a Yorkist Princess, Elizabeth, daughter of Edward IV and uniting the two warring households once and for all.

Richard’s body was paraded unceremoniously and ignominiously through the streets to prove his death and show the colours of the new king. Henry further cemented his grip by marrying a Yorkist Princess, Elizabeth, daughter of Edward IV and uniting the two warring households once and for all.

Henry’s ascendance to the throne marked a new style of leadership, not always successful. He realised that a common sense approach to leadership was to protect his valuables in order to keep the crown in a healthy and strong economic position. He successfully stopped the sprawl of the nobility, only handing out titles to people who had really earned them and stopping some automatic inheritance, meaning for a time at least, there was little threat to power from large families who had an eye on titles and money. The Tudor line ruled for over a century in a relatively, though not completely peaceful time.